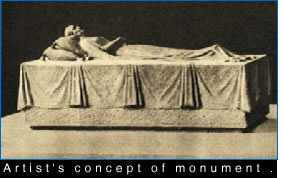

On July 17, 1952, when Evita was dying, the Argentine Congress passed law 14.124, authorizing the construction of a monument dedicated to the workers of Argentina. A  chapel within the monument would contain a crystal and silver casket holding the remains of Eva Perón. Leone Tommasi, the famous Italian sculptor who had made the statues for the frontispiece of the Fundación Eva Perón-now the Facultad de Derecho-was commissioned to sculpt the statues for the monument and Carlos Pallarols, Juan Carlos’ father, commissioned to make the silver covering for the casket. chapel within the monument would contain a crystal and silver casket holding the remains of Eva Perón. Leone Tommasi, the famous Italian sculptor who had made the statues for the frontispiece of the Fundación Eva Perón-now the Facultad de Derecho-was commissioned to sculpt the statues for the monument and Carlos Pallarols, Juan Carlos’ father, commissioned to make the silver covering for the casket.

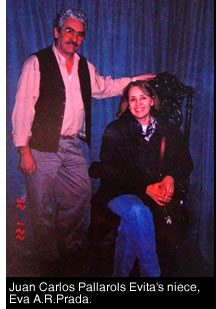

Dolane Larson interviewed Juan Carlos Pallarols on August 1, 2003, in his workshop in San Telmo, the colonial neighborhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Before transcribing the interview, we offer you an excerpt from the biography of Juan Carlos Pallarols. To read the complete biography and to learn more about this talented world famous silversmith, visit his web site, www.pallarols.com.ar

“Juan Carlos Pallarols was born in Banfield, Buenos Aires Province, in 1942, the fourth son of Carlos Pallarols Cuni, a well-known Catalan silversmith. From an early age he began his apprenticeship in what would become his lifetime vocation and profession. His formation next to his father Carlos and his grandfather José (excellent silversmiths, draftsmen and painters) together with his innate curiosity enabled him to become an autodidact in his profession. Juan Carlos analyzes and studies each project, reads and observes, compares styles, techniques and usages. His innovative spirit and his investigative capacity have earned him national and international fame.”

The text of the interview:

The story I am about to tell forms part of my youth. When Eva Perón died [in 1952], I was twelve years old. Later I met Doctor Jorge Taiana, I knew Paco Jamandreu, her dressmaker, I knew Captain Ricardo Pablo Anchorena, her aide-de-camp, very well, I knew Delia Parodi, and many other people who had worked with my father, including the Minister of Public Works at the time of the monument. From all of them I extracted information which I added to the experiences I had lived myself. The story I am about to tell forms part of my youth. When Eva Perón died [in 1952], I was twelve years old. Later I met Doctor Jorge Taiana, I knew Paco Jamandreu, her dressmaker, I knew Captain Ricardo Pablo Anchorena, her aide-de-camp, very well, I knew Delia Parodi, and many other people who had worked with my father, including the Minister of Public Works at the time of the monument. From all of them I extracted information which I added to the experiences I had lived myself.

The story is as follows:

Eva Perón traveled to Europe [in 1947] and during her trip she saw Les Invalides, the tomb of Napoleon [in Paris] and thought that it would be an important monument [which could be copied] and where the remains of the workers who died in 1945 could be placed. This remained as a project. When Eva Perón became mortally ill and died, this project was taken up to be made into a monument to workers; within the monument a chapel would be constructed and the mortal remains of Eva Perón would be kept there. The idea was that she would be embalmed, a task which Pedro Ara was already carrying out. The body would be in a crystal casket and the casket would be covered with a fine layer of silver in the form of Eva Perón as though she were asleep, her arms crossed. The idea was that on each July 26 [the day Evita died in 1952], this cover would be raised so that people could see her body, a Mass would be said, and homage would be rendered. Today this seems a little “strange,” but at that time it was very common to display great leaders, great personalities. People were not so afraid of death, did not reject death so much. In other words, funeral art was much more prevalent, and included saints, monarchs, great leaders of the left and of the right... all the important people. You can see it in the tombs of the Catholic Kings, in England, in France, everywhere.

So the idea was that this cover could be raised; therefore, it had to be a very fine covering of silver so that it would not be too heavy and could be easily raised. At the time my father was famous because he was very well-versed in that technique, so he was chosen to carry out this project. He was summoned, he presented the project, and the Minister Dupeyron and Señora Delia Parodi came to see him. My father designed the project and talked to Pedro Ara, talked to a sculptor named Tommasi. I remember the people who came to my house [when] I was a boy. So the work was undertaken. The mask was made from the body of Eva Perón which was in the CGT [Confederacón General de Trabajo, labor union headquarters]. Sometimes I would go with my father and I remember once he left in a state of shock. I don’t know what was inside. After fifty years I returned to the CGT to attend an inauguration of a museum which was opened there. So the idea was that this cover could be raised; therefore, it had to be a very fine covering of silver so that it would not be too heavy and could be easily raised. At the time my father was famous because he was very well-versed in that technique, so he was chosen to carry out this project. He was summoned, he presented the project, and the Minister Dupeyron and Señora Delia Parodi came to see him. My father designed the project and talked to Pedro Ara, talked to a sculptor named Tommasi. I remember the people who came to my house [when] I was a boy. So the work was undertaken. The mask was made from the body of Eva Perón which was in the CGT [Confederacón General de Trabajo, labor union headquarters]. Sometimes I would go with my father and I remember once he left in a state of shock. I don’t know what was inside. After fifty years I returned to the CGT to attend an inauguration of a museum which was opened there.

But Father worked on this silver covering for three years. And in 1955 came the Revolution which deposed Perón. All [Peronista] monuments were forbidden by law; anything that was related to Perón’s government had to be destroyed.

My father was forced to destroy the work he had done or face severe penalties if he did not. So my father melted down all the silver components. He sold the material and recovered some of his expenses, and the molds made of clay and plaster of paris he broke up and hid. For almost fifty years, for over forty years, the molds were hidden. They were hidden in Temperley, a town in the South, afterwards in Burzaco, and finally in the countryside. They were hidden in boxes until in 1990, more or less, 1988; around that time, I uncovered them and started to restore them and exhibit them to the public.

My father was very traumatized emotionally, he was very sad, he was very, very hurt because his most important work had been destroyed. This brought him very serious health problems; finally he had an attack and he died young, before he reached the age of sixty. He was told to initiate a lawsuit so as to recuperate the money and the time he had invested. But my father was a good person, grateful to this country which had opened its doors to him when things were very bad in Europe because in Europe there was hunger, there was much poverty. The War of 1914, WWI had come to Europe, there were many problems there and Argentina offered a peaceful refuge. He started a family here and he stayed. He did not want to sue but he lost his house because he had several mortgages, he had taken out loans to finance the construction, and his house on the 600 block of Aguero Street in Lomas de Zamora was auctioned off. All this, plus the destruction [of his work] caused him so much harm that my father died very young. Dr. Taiana told me about the mask, and my father also remembered-and this I want to confirm with Dr. Taiana’s wife so as to have a more important witness than I am. Dr. Taiana told me that paraffin was injected into Eva Perón because she was very thin, very emaciated, and her face was molded so that she looked more healthy; then the mold was taken and that mask is the one Cristina has [in the Museo Evita] which I loaned to her and I have the original here in the museum [of Mr. Pallarols]. This is the more or less brief story that I have to tell.

One day I saw my father come out [of the CGT] extremely shocked. He didn’t know I was listening when he told how he had seen Eva Perón hanging vertically, I don’t know if head up or head down, but that they had injected something, a liquid or something and she was in that position so that the liquid would run throughout her body which was then submerged in hot paraffin-I don’t know why-but Dr. Taiana said that it was to fill out the body which would than be molded. One day I saw my father come out [of the CGT] extremely shocked. He didn’t know I was listening when he told how he had seen Eva Perón hanging vertically, I don’t know if head up or head down, but that they had injected something, a liquid or something and she was in that position so that the liquid would run throughout her body which was then submerged in hot paraffin-I don’t know why-but Dr. Taiana said that it was to fill out the body which would than be molded.

The paraffin, the wax, totally covered the body, and didn’t let any air in so that there was no type of oxygenation, nor contamination.

Dr. Taiana told me that he found out that Eva Perón was ill because a maid called one day and told him, “Doctor, several times when I have changed the sheets, I have found blood on them; one can see that the Señora has small hemorrhages or she has been injured.”

Then Dr. Taiana called Eva Perón and he told her, “Señora, something is happening to you because So-and-So told me that you are having hemorrhages. Something is wrong.You must have an examination immediately to see what is wrong.”

And she said, “No, I can’t now, I’m too busy, I have too much work,” because she was in the middle of something; I don’t know if it was the vote for women or what. And [Taiana] said, “Señora, if you don’t take my advice and start a treatment, I will have to tell the President, the General.”

Evita replied, “Then the General will lose a minister.” Evita replied, “Then the General will lose a minister.”

Taiana said, “I prefer for the General to lose a minister than to lose his wife.”

Evita answered, “You little old tattletale.”

So he pressured her to start to take care of herself but she didn’t want to because she worked until 10:00 or 11:00 P.M. and she didn’t have time to take care of her health. A doctor came from the United States [George Pack, who operated on her].

Then they submitted her to a very cruel treatment-they burned her alive. They brought a technology [radiation]... which [Taiana] later regretted very much because he said, “I felt like we were burning her alive.” He felt remorse that he didn’t prevent it. “What that woman suffered was tremendous,” Dr. Taiana said.

End of the interview.

To learn more about Juan Carlos Pallarols and the crystal and silver casket, see Newsweek, ed. Argentina, 11/29/06 (pgs. 16-17). |