|

Evita versus Evita

by Dolane Larson

“Life is like a wheel. Sometimes you are on the top, sometimes on the bottom.”

Evita’s mother, Juana Ibarguren

"Truth is the daughter of time, not of authority."

Francis Bacon

Truth...

|

Eva Duarte

Eva Duarte, born in Buenos Aires Province in 1919, spent her childhood in the small town of Los Toldos and her early teens in the city of Junín. As a young teenager she left school after sixth grade, determined to follow her childhood dream-to be an actress. In April 1934 one of Junín’s local newspapers published a small paragraph: “Our neighbor señorita María Eva Duarte has left for the capital [Buenos Aires] where she will act as a replacement for Miss Kelly, in Radio La Nación, L.R.6. She will debut this evening or tomorrow at 5:00.”1

Eva Duarte, born in Buenos Aires Province in 1919, spent her childhood in the small town of Los Toldos and her early teens in the city of Junín. As a young teenager she left school after sixth grade, determined to follow her childhood dream-to be an actress. In April 1934 one of Junín’s local newspapers published a small paragraph: “Our neighbor señorita María Eva Duarte has left for the capital [Buenos Aires] where she will act as a replacement for Miss Kelly, in Radio La Nación, L.R.6. She will debut this evening or tomorrow at 5:00.”1

After her debut, Evita returned to Junín.

Many of Evita’s biographers state that she went to Buenos Aires in the company of Augustín Magaldi, a tango singer. However, “Newspapers in Junín, Democracia, La Verdad, El Amigo del Pueblo and Orientación do not register the presence of Magaldi in Junín in the years 1934-1935. Would they omit his presence when their pages take note of all the artists who arrived from the capital to entertain in the Teatro Italiano, in the Crystal Palace or in the social clubs? Certainly not. According to Roberto Dimarco, the singer [Magaldi] was there on three occasions: April 1929, December 1936, and March 1938. During those years Eva was not in Junín.”2

Eva and Magaldi were not in Junín at the same time, but they may have met in Buenos Aires since both worked for Radio París.3

In a 1944 interview, Eva Duarte said, “I always remember with profound emotion my first appearance on the radio. I was very young and I started to recite in front of the microphone of Radio Nacional. I still don’t understand how I could overcome the nervousness of my debut.”4

“If she had to fight to overcome family resistance; if the guardianship of her brother Juan, finishing his military conscription in the capital at the time, calmed anxieties; if the days were difficult and the nights long, Evita was facing her new reality; the step had been taken and there would be no return.”5

At an early age, Evita took charge of her own destiny. “I have always lived in freedom. Like the birds, I have always liked the free air of the forests. I have not even been able to tolerate that servitude that comes with being in your parents’ house or the town of your  birth. I have wanted to live on my own and I have lived on my own.”6

birth. I have wanted to live on my own and I have lived on my own.”6

Eva Duarte spent years as an actress in Buenos Aires, first in the theater, then in radio and on screen. At the beginning of her career, she lived in inexpensive boarding houses, some in La Boca, an immigrant section of Buenos Aires near the Riachuelo. Later she was able to rent apartments in downtown Buenos Aires and eventually buy one. She was not born in a slum, nor did she live in a slum after she moved to Buenos Aires.

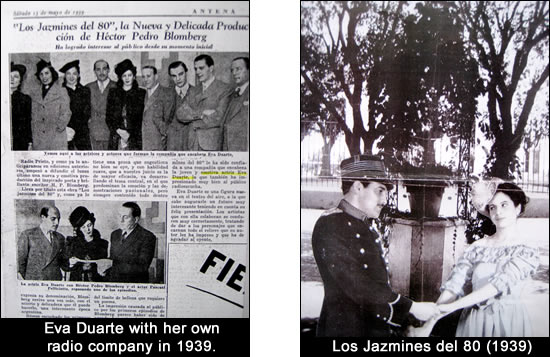

By 1939, she had her own company of radio stars and by 1943 had begun her Heroines of History radio program, its biographies of famous women a foreshadowing of her future. In 1944, she fell in love with and in 1945 married Colonel Juan Perón, candidate for the presidency of his country.

Eva Perón

As First Lady of Argentina, Eva Perón became one of the most powerful women of her time-although the reins of her power remained firmly in her husband’s hands. She held no elected office, yet she delved below the surface of her people’s lives to reach the depths of their need. Many remember Evita for those she helped-women who voted for the first time; seniors; abandoned women and children; the ill and marginalized of her own country, their free fall broken by the safety nets she created; those around the world, victims of poverty and natural disasters who received medicine and assistance from the doctors and nurses of the Fundación Eva Perón. Evita was not a saint, but, like most of us, a flawed human being. Yet for seven years, the time that was given her, she sacrificed her health, her private life and many hours that should have been dedicated to sleep-because she loved her descamisados. That many still love her is shown by the flowers and notes attached every day to the door of the Duarte family mausoleum in Buenos Aires’ Recoleta cemetery, remembrances often left by the children and grandchildren of those whose lives she touched.

Primer Gobierno Peronista

During the “first Peronista government” (1946-1955), film and print images of Evita flooded every corner of the country. In many humble homes, candles and flowers surrounded her picture. Although diminished by her death in 1952, the Fundación Eva Perón continued to function and her descamisados continued to address their letters to her.

Then came the September 1955 coup d’état that overthrew Perón. General Lonardi assumed power after Perón went into exile, promising “Neither conquerors nor conquered.” Lonardi was soon replaced by military officers who wanted the Peronistas to know that they had been conquered and would be ground under the generals’ boots. After General Aramburu assumed the presidency, workers were shot, the Fundación was looted, Evita’s family went into exile, her body disappeared and the Presidential Residence where she had died was torn down. The military government passed Decree 4.161/55 prohibiting even the mention of the names Perón and Evita or any public or private display of pictures, songs, insignia (anything related to Peronismo) on pain of imprisonment. Many historical documents and pictures were burned; others were hidden in the hopes that someday some semblance of sanity would return. Evita’s Fundación Eva Perón was dismantled. Adela Caprile, a member of the committee set up to liquidate the Fundación’s assets, stated, “It was...not a fraud. Evita cannot be accused of having kept one peso in her pocket... I would like to be able to say as much of all the ones who collaborated with me in the dissolution of the organization.”7 Minister of Finance Ramón Cereijo had scrupulously administered the Fundación’s finances to account for every cent.8

La Resistencia Peronista

During the “Resistencia Peronista” mounted police broke up Peronista political rallies and Neptune vehicles sprayed the crowds with colored water (so people could be identified and picked up). In 1958, the military allowed elections. Although the Peronista Party was banned from participating, Peronistas voted for the Radical Party candidate, Arturo Frondizi. With their help, he won. When the time came to elect governors, President Frondizi allowed Peronistas to vote for their own candidates. On March 18, 1962, the Peronista candidates for governor won in fourteen of the eighteen provinces (including the largest, Buenos Aires Province). On March 29, a military coup annulled the elections, outlawed the Peronista Party (again) and arrested Frondizi.9 Until 1973, except for Arturo Illia10, either figurehead presidents or generals governed Argentina.

Peronistas wore tiny symbolic forget-me-not pins: the workers remembered well what they had lost. Each July 26, Peronista women marked the anniversary of Evita’s death with Masses, searching for priests willing to pronounce her name in public (not all would). An open wound contaminated the political landscape. What had the military done with Evita’s body? Had they burned it, thrown it into the Río de la Plata to be swept away by the current or buried it in an unmarked grave? Many nights Evita’s mother cried herself to sleep because she could not answer those questions. Although she wrote to presidents and popes and sometimes obtained interviews with people who might have known, no one would tell her anything.11 The Peronistas did not forget Evita but the rest of the world did. From 1952 until 1971 “there were almost no popular or scholarly books or articles...no visual media treatments” of Evita.”12

In exile since 1955, Perón travelled to different Latin American countries before settling down in Franco’s Spain. He built a home in the Madrid neighborhood of Puerta de Hierro and in 1961 he married Isabel Martínez, an Argentine he had lived with since he met her in Panama (to remain in Spain, Perón met Franco’s demand that he marry Isabel; he ignored Franco’s demand to abstain from politics).

In 1957, the military government arranged to send Evita’s body to Italy. In September, retracing a journey she had made in life, her body was taken to Milan and buried in the Musocco Cemetery. At last “María Maggi de Magistris” (twenty-one letters=María Eva Duarte de Perón) received Christian burial. In 1971, the grave was opened, and the body of Eva Perón travelled to Puerta de Hierro in Madrid. There her husband and her surviving sisters Blanca and Erminda gazed in horror at the slashes, burns and abuse13 inflicted on the body by its custodians.14However, in answer to many prayers, the body had not been destroyed-and it had received Christian burial.

Perón died in July, 1973, leaving Isabel, his wife and vice-president, to govern the country. In 1974, she brought Evita’s body back to Buenos Aires. Although Isabel had been constitutionally elected, by 1976 her disastrous government ended in another military coup. During the 1970s and 1980s the military was responsible for the deaths of thousands of Argentines who disappeared during the “Dirty War” and of hundreds of young soldiers who fought in the 1982 Islas Malvinas/Falkland Islands War. Democracy did not return to Argentina until 1983 with the election of the Radical Party candidate, Raúl Alfonsín.

The American Press

During the 1940s and 1950s, the golden age of American print journalism, the State Department used the “prestige press” (the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Time and Newsweek) to gauge and influence public opinion.15 These most-read publications had not been kind to Evita. During Perón’s first presidency, Time was banned more than once for remarks ranging from the snide (quoting an Argentine Embassy official after Evita left Italy: “I don’t know whether I’m gladder that the rain came or that Eva has gone”16) to the scoffing (“It was not the humble swamp from which the Argentine rainbow rose that earned her the haughty looks of B.A.’s aristocrats; it was the murky clouds through which she had climbed to arch so gracefully over their heads”17 ).

Some articles were so “savage” and “scurrilous” that the Argentine Embassy placed an appeal to journalists in the New York Times, asking for fairness and decorum, stating that the “nauseous attacks on Evita were unworthy of the American Press.”18

During the early 1970s, influenced by the enduring devotion to her in Argentina, the media portrayed Evita as a “sincere, fully politicized advocate for the disadvantaged.”19 Posters put up by Argentina’s powerful labor unions commemorated Evita as the workers remembered her (a flower that blossomed into fruit). The middle-class guerrilleros intent on overthrowing the military regimes preferred an Evita Revolucionaria.

A new Evita narrative “imbued her with a feminist, anti-patriarchal fire reflective of the contemporary moment in the United States...her illegitimate birth...cited as proof of her political legitimacy and desire for equality.”20 Time wrote of “a sleek and inspiring Evita Perón, a flag bearer of the workers”21 and Newsweek warned, “You can joke about Perón but don’t ever try it with Evita.” A new assessment gave Evita a larger place in history than Perón, an idea that pleased Perón not at all. “Journalists preferred Evita not because of her politics but because in the end she appeared as a magnanimous, courageous, and tragic figure, more sinned against than sinning...a more courageous person than her husband.”22

“Hooked on the story of her life” after listening to the BBC radio program “Legends in Our Lifetime,” Tim Rice convinced composer Andrew Lloyd Webber “that a musical about Evita would be an intriguing project.”23 Unfortunately, Marysa Navarro’s well-documented biography had not yet been published. In 1974, fourteen years after Evita’s death, Rice visited Argentina. “Content to maintain a low profile,”24 he did not interview people who had known Evita (many of whom were still living), nor did he conduct any objective indepth research. Instead, when he returned to the US, Rice consulted two women whose out-of-print books “were essentially extended anti-Peronista gossip columns.”25 Fleur Cowles (Bloody Precedent) and Mary Main (The Woman With the Whip) “aimed their vitriol at Evita because of her involvement in a political movement they found morally repugnant.”26

Mrs. Cowles, one of a group of American editors and publishers invited in July 1950 to the Casa Rosada to meet Perón, asked if her group would also be able to “pay their respects to Mme. Perón.”27 No, she was told, Evita was not in Buenos Aires; she was busy with social welfare projects outside the city. Mrs. Cowles insisted: “What shall I tell the Americans who ask me about Madame Perón?” After a whispered conversation with Perón, a messenger left. Later, when Evita appeared, she surprised the editor of Flair magazine. Instead of an “over-dressed hussy, a flashy companion,”28 Mrs. Cowles found herself facing “a trim, obviously busy woman, with an air that was efficient, composed...elegantly dressed in a navy-blue suit by Jacques Fath...who came in quietly [and] smiled carefully at all of us.” Mrs. Cowles asked her, “What one thing do you want me to remember you by when I go back home?” Evita replied, “If you stay behind tonight I will show you.”29 Instead of going to the American Embassy dinner-dance, Fleur Cowles accompanied Evita to the Teatro Colón and watched as Evita handed out pensions for seniors over seventy. Mrs. Cowles had observed how Perón’s face lit up when told that Evita was on her way, how often Evita smiled at her husband, how courteous they were to each other, how Perón “kissed her good-bye-on her forehead,”30 and concluded, [Perón’s] pride in her is totally abstract, as if in relation to any possession that had proved its value in the most impersonal sense.” In Bloody Precedent ( with Juan Manuel and Encarnación Rosas as “the Precedents”) Mrs. Cowles used many words to describe Evita, some subjective (opportunistic, manically ambitious, bitter and determined, spiteful, a Queen Bee), others more objective (a strained tired look, over-taxed, nervous, energetic, pallid, the greenness of her skin a warning of a seriously sick woman)31.

Mary Main, the daughter of British parents in Buenos Aires and product of a finishing school in England, had moved to the United States in 1941. In 1950, Doubleday asked her to write a biography of Eva Perón. She travelled to Buenos Aires, never met Evita (she saw her twice, once as Evita entered the Teatro Colón32), conducted her interviews in secret, and used the pseudonym María Flores because she feared retaliation. Years later, the Opera Evita revived interest in The Woman With the Whip, and the book was reprinted in 1977, 1980, and 1996. As Mary Main no longer needed to fear retaliation, she could have, but did not, document her sources. In her new forward, she did blame Evita for the military’s Dirty War and all the other ills that afflicted Argentina after her death in 1952: “she and Perón set in motion those forces which were to destroy their country. No, it is not for Evita that Argentina should cry! It is for all those Argentinians who have, since her time, and in increasing numbers, mysteriously disappeared, and whose deaths remain unaccounted for.”33

Evita in London

Thanks to Julie Covington’s interpretation and “sweet plaintive voice,”34 the London studio recording presented a humanized, very feminine Evita, who, although she stepped outside of society’s boundaries, had a heart of gold.35 The real Evita’s love for her descamisados and theirs for her found a place in Julie Covington’s interpretation.

When the Opera arrived in theaters and critics complained that the it softened Evita’s image as the wife of a fascist dictator, Rice defended his emphasis on celebrity: “If your subject happens to be one of the most glamorous women who ever lived, you will inevitably be accused of glamorizing her. The only political messages we hope will emerge are that extremists are dangerous and attractive ones even more so.”36

American Version

The London criticism alerted Rice and Webber: for the musical to succeed in the United States, they would need to align their opera image with the image created by the State Department and the “first tier” US media:37 Evita as “a cruel Latin American Lady Macbeth.”38 Fleur Cowles and Mary Main were more than willing to help39. Indeed, “Rice appeared to have written new lines and rewritten others with Fleur Cowles perched on his shoulder.”40 Evita became a sharp-featured anti-heroine and Perón more menacing. To further scrape away any sympathy for Evita or Perón, new songs were added and the original ones adapted, as cited in Victoria Allison’s White Evil: Peronist Argentina in the US Popular Imagination Since 1955:

- “In the London version ‘A New Argentina’ replaces a corrupt government: ‘A new Argentina/The old one’s gone sadly wrong/A new Argentina/The voice of the people rings out loud and strong’

- The US version shows “a brutal and dangerously proletariat movement: ‘A new Argentina/We face the world together and no dissent within [while clubbing dissenters].’41

- The London Evita sang, “I only want variety of society” (as in social justice).

- The American Evita sang, “I only want variety-notoriety!”

- The US Evita conforms to the Cowles/Main creation: “a shrill-voiced, grasping, sneering, megalomaniac,”42 an imperious “Queen Bee”, as Cowles liked to call her.43

Not everyone was taken in by Rice/Webber-Cowles/Main attempt “to take the appeal out of Evita.”44 In a New York Times “Stage View” article, critic Walter Kerr wrote that Evita had taken a bold step backward-into a medieval morality play. He quoted Rice/Webber as saying, “Eva Perón was a fascinating woman. She did any good things...and she was also a megalomaniac, corrupted by all that power. We tried to show both sides.” Kerr points out why and how they failed. First, “Morality plays don’t have characters, certainly not characters of any complexity. They have figureheads, not mixtures of flesh and blood, good and evil, charm and corruption. They are simply walking Capital Letters called Ambition, Vanity, Pride.” Second, in employing an outmoded method, the play became “emotionally icy, psychologically monochromatic, a cut-and-dried sermon with capital letters to burn.”45

Kerr wrote, “Ambition is the key to Evita.” The “American Evita” is never allowed to be sympathetic; she is always predatory and cynical. “So much for both sides,” Kerr commented. He pointed out “the roots of sterility that haunt the entire exercise,” with its melodies that are “mainly afterthoughts.” The motion pictures and stills of the real Evita provide more hints about her personality “than anything that happens on stage. But you see what we’re dealing with, once again. Ghostly substitutes.”46

In 1996, Alan Parker released the Madonna movie Evita, more connected to the London studio version than to the Broadway one. In the Parker movie, Perón provides fatherly support, Che makes amusing comments and Evita dies brokenhearted: all she ever truly wanted was to be loved.47

Back into a Morality Play

Rice and Lloyd Webber’s musical never meant to present the historical Evita. In their opera, the figure of Evita becomes a commodity, a celebrity created to entertain and sell merchandise, not a real person who tells her own story. The Argentine army and oligarchy, her enemies in real life, serve as a raucous chorus while, in the earlier versions, Che Guevara becomes a secondary narrator.48 Although Che and Evita occupied the same planet for twenty-four years, Che never met Evita. The first Opera converted a man who had the courage to die for his convictions (whether you agree with them or not) into a peddler of insecticides49. The 2012 version sheds the “Guevara guerrillero” image and “Che” becomes an “Everyman skeptic-narrator.”50 We return to a Walter Kerr view of Evita peopled with stock characters: an Everyman (the quintessential medieval morality play) with its personifications of vices (pride, avarice), objects (money) and activities (death). Perhaps courage in the face of death is its only virtue.

Rice and Lloyd Webber’s musical never meant to present the historical Evita. In their opera, the figure of Evita becomes a commodity, a celebrity created to entertain and sell merchandise, not a real person who tells her own story. The Argentine army and oligarchy, her enemies in real life, serve as a raucous chorus while, in the earlier versions, Che Guevara becomes a secondary narrator.48 Although Che and Evita occupied the same planet for twenty-four years, Che never met Evita. The first Opera converted a man who had the courage to die for his convictions (whether you agree with them or not) into a peddler of insecticides49. The 2012 version sheds the “Guevara guerrillero” image and “Che” becomes an “Everyman skeptic-narrator.”50 We return to a Walter Kerr view of Evita peopled with stock characters: an Everyman (the quintessential medieval morality play) with its personifications of vices (pride, avarice), objects (money) and activities (death). Perhaps courage in the face of death is its only virtue.

Life and choice presented Evita with two roles: “Eva Perón, the wife of the President of the Republic, whose work is simple and agreeable, a work of holidays, of receiving honors, of gala events; the other, Evita, the wife of the Leader of a people who have deposited in him all their faith, their hope and all their love. On a few days of the year, I represent the role of Eva Perón...neither difficult nor disagreeable.

On the great majority of the days I am, on the other hand, Evita... a difficult role and one in which I am never totally happy with myself.”51 Eva Perón, First Lady, went to the Colón Opera House wearing a Dior evening gowns adorned with jewels and the Legion of Honor. Evita, Lady of Hope, wore tailored suits when she spoke to her descamisados from the balcony of the Casa Rosada or met with workers, women, children and seniors in a Ministry of Labor office that used to be Perón’s. The Opera Evita appears on the balcony of the Casa Rosada in an evening gown and jewels-a contradiction of roles, expressing the “apparently contradictory feelings Lloyd Webber and Rice have for Eva Perón.”52

On the great majority of the days I am, on the other hand, Evita... a difficult role and one in which I am never totally happy with myself.”51 Eva Perón, First Lady, went to the Colón Opera House wearing a Dior evening gowns adorned with jewels and the Legion of Honor. Evita, Lady of Hope, wore tailored suits when she spoke to her descamisados from the balcony of the Casa Rosada or met with workers, women, children and seniors in a Ministry of Labor office that used to be Perón’s. The Opera Evita appears on the balcony of the Casa Rosada in an evening gown and jewels-a contradiction of roles, expressing the “apparently contradictory feelings Lloyd Webber and Rice have for Eva Perón.”52

For the first time Evita is played by an Argentine who knows the Buenos Aires Evita knew. “I feel very connected with the story,” said Elena Roger. Some of her family members were Peronistas who saw the positive side ( vote for women; improvement in the workers’ lives). Others saw a more sinister side ( the time Perón dedicated to young women after Evita’s death). “I try to understand,” Elena Rogers concludes, “and not judge.”53

| ... And Returns to Reality |

In 1951, Josephine Tey’s book, Daughter of Time, inspired people to look beyond the Tudor myth in search of the historical Richard III. The team of investigators at the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Históricas Eva Perón continues to challenge myths and bring into sharper focus Evita, a daughter of time.

The INIHEP is publishing a series of books, based on historical documents and oral history interviews, conducted by dynamic and talented young investigators. For those interested in the real Evita, a list follows:

- Mi biografía política (2006) by Ana Carmen Macri; Diputada Nacional;

- La Embajadora de la Paz: Evita’s trip to Europe in 1947 (2008) by Damian Cipolla, Laura Macek and Romina Martinez;

- Memorias de joven militancia (2008) by Duilio Brunello, Senador Nacional, active in the Peronista Resistance;

- Arreando Recuerdos (2009) by Rodolfo Decker, Diputado Nacional;

- La enfermera de Evita (2010) by María Eugenia Alvarez, Evita’s nurse;

- Evita de Los Toldos (2011) by Investigaciones Históricas team;

- La Constitucion Social de 1949. Hacia una democracia de masas by Santiago Regolo.

Noemí Castiñeiras, El Ajedrez de la Gloria: Eva Duarte Actriz (Buenos Aires: Catálogos, 2002), 20.

Ibid., 27.

Ibid.

Ibid, quoted in Radiolandia, September 2, 1944.

Castiñerias, 28.

Eva Perón, La razón de mi vida (Buenos Aires: Peuser, 1951),243. (my translation)

Alicia Dujovne Oritz, Eva Perón (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 236. See “Where did the money come from?” on this website for the sources of the FEP revenue.

Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro, Evita: The Real Life of Eva Perón (New York: W.W. Norton &

Company, 1996), 120.

Frondizi was taken to the same island prison of Martín García where Perón had been imprisoned in

October, 1945.

Although the Peronista Party, the country’s largest, was proscribed, Illia was elected President. He governed from October 1963 until the generals removed him in June 1966. Illia is now considered one of

Argentina’s most honest and efficient Presidents.

Evita’s mother died months before Evita’s body was returned to Perón. Perhaps it is just as well she did

not see the savage mutilation and torture the military inflicted on her daughter’s body. In 1955, when Evita’s

family was in exile, Juan Duarte’s tomb in the Recoleta was opened and his body also desecrated by the

military.

Victoria Allison, “White Evil: Peronist Argentina in the US Popular Imagination Since 1955,” American Studies International, February 2004, 2. [online EBSCOhost].

Perón documented the profanations with photographs considered too incendiary to be published; Evita’s sister Erminda described the profanation of the body in her book Mi Hermana Evita.

See E. Duarte: My Sister Evita “September 5, 1971,” for Erminda Duarte’s description of the Evita’s body.

Steven F. White, “De Gasperi through American Eyes: Media and Public Opinion 1945-53,” Italian Politics and Society, Fall/Winter 2005, 11 (online).

“Little Eva,” Time, July 14, 1947, 33.

Ibid.

The Land That England Lost: Argentina & Britain, a Special Relationship. Edited by Alistair Hennessy and John King. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992, p.239.

Allison, op.cit.,4.

Ibid.

Time and Newsweek quotes cited in Allison, op cit., pg. 4.

Allison, op.cit., 4.

Ibid.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, Evita: The Legend of Eva Perón (New York: Avon, 1979), Introduction (n/p).

Allison.,4-5.

Ibid, 6.

Fleur Cowles, Bloody Precedent (New York: Random House, 1952), 170.

Ibid, 170-171.

Ibid.,171.

Ibid, 173.

Ibid, 172-173.

Mary Main, The Woman With the Whip (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1980),10-11.

Ibid.

Allison, p.5.

Ibid.

Ibid, 6-7.

“Nearly all the literature on Peronism takes the form of indictment...The denigration has reached a scale that historians must resist accepting it at face value and pose instead the scholarly question ‘Why is it there?’ Most of the time Argentina is not central to the world’s concerns, so how has it come about that on one of those are occasions when an Argentine politician [Perón] became well-known, it took the form of rabid vituperation?” The Land That England Lost: Argentina & Britain, a Special Relationship, p.93.

Allison, op. cit., 7.

And did well for themselves by helping. Their books were reprinted and Evita (although not a friend) was on the cover of Fleur Cowles’ new book, She Made Friends-and Kept Them.

Allison, op. cit., 7.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Cowles, Bloody Precedent, 191.

Walter Kerr, “ ‘Evita’ Takes A Bold Step Backward,” New York Times October 7, 1979.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Allison, 9.

Allison, op.cit., 5.

As a medical student [Che] had at one point studied tripical diseases which led him to attempt the commercial manufacture of an insecticide in 1950.” Lloyd Webber and Rice op.cit., n/p.

Matthew Murray, “Evita,” Talkin’ Broadway (New York), April 5, 2012 (online).

Eva Perón, op.cit., 86.

Mark Kennedy, “Evita Review: Ricky Martin Is Easily The Best Thing About This Revival,” Associated Press (New York: April 5, 2012)

Joyce Waldler, “Don’t Cry for Her, Argentina; She Landed the Big Role,” The New York Times (New York: March 22, 2012). The paragraph about Elena Roger is taken from this article.