|

“Foreign Aid for America!”

Don’t Tell the Russians

by Dolane Larson

|

In September 1949 Mrs. Fay Vawters began again to make the rounds of the Washington embassies. After a hot summer, autumn stood at the doorstep of the Children’s Aid Society and with autumn came school. Although built on land donated by the southern state of Maryland, Washington did experience cold spells, below zero temperatures-even occasional blizzards. If the Reverend Ralph and Mrs. Fay Vawters did not want “their” children to shiver on the way to school, the time had come to ask for donations to buy warm winter coats and sturdy shoes. Even with over a thousand children to feed and clothe, Mrs. Vawters harbored no grandiose expectations. “We had five or ten dollars in mind. We solicit thousands of people for help.”1

In September 1949 Mrs. Fay Vawters began again to make the rounds of the Washington embassies. After a hot summer, autumn stood at the doorstep of the Children’s Aid Society and with autumn came school. Although built on land donated by the southern state of Maryland, Washington did experience cold spells, below zero temperatures-even occasional blizzards. If the Reverend Ralph and Mrs. Fay Vawters did not want “their” children to shiver on the way to school, the time had come to ask for donations to buy warm winter coats and sturdy shoes. Even with over a thousand children to feed and clothe, Mrs. Vawters harbored no grandiose expectations. “We had five or ten dollars in mind. We solicit thousands of people for help.”1

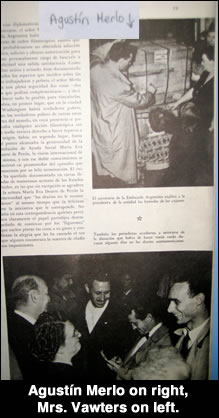

When she telephoned the Argentine embassy asking for a donation “to help clothe the needy children of the nation’s capital as they prepared to return to school,” labor attaché2 Agustín Merlo requested and received Embassy authorization to take charge of Mrs. Vawters’ request. “He asked us to send him a letter to confirm that we had solicited [a donation]. This is a routine procedure,” Mrs. Vawters explained.3

Agustín Merlo did not follow routine procedures. Instead, he contacted Eva Perón, the wife of Argentina’s President, and head of the Fundación Eva Perón. He did not ask for money but for winter clothes and shoes for 600 children, not an unusual request for a Foundation that was sending aid to countries worldwide4

Agustín Merlo did not follow routine procedures. Instead, he contacted Eva Perón, the wife of Argentina’s President, and head of the Fundación Eva Perón. He did not ask for money but for winter clothes and shoes for 600 children, not an unusual request for a Foundation that was sending aid to countries worldwide4

November and December passed and the Reverend and Mrs. Vawters heard no more from the Argentine Embassy.

By January, the winter clothes and shoes, all made in Argentina, had been packed in crates and were winging their way to the United States. “This plane that will soon arrive in  the United States represents the kindness of our leader and what we are capable of doing for the dispossessed, no matter where they are,” Evita wrote. In her “tumultuous handwriting” she added, “May this action and this aid which we offer with all respect and affection to the great people of the United States serve as an example as we humbly send them our little grain of sand to help.”5

the United States represents the kindness of our leader and what we are capable of doing for the dispossessed, no matter where they are,” Evita wrote. In her “tumultuous handwriting” she added, “May this action and this aid which we offer with all respect and affection to the great people of the United States serve as an example as we humbly send them our little grain of sand to help.”5

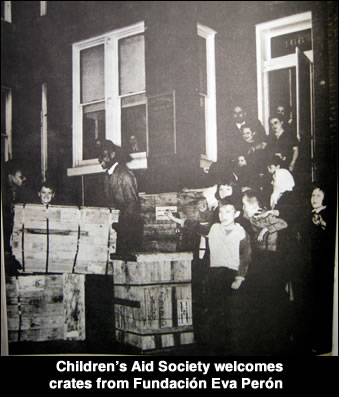

Seven days before President Truman’s January 20 inauguration, the six crates arrived, addressed to Agustín Merlo and bearing the label “Envío de la Presidencia de la República Argentina.” Mr. Merlo contacted the Vawters on Thursday, January 13, to say that winter clothing and shoes for 600 children had arrived from the Fundación Eva Perón and would be delivered to the Children’s Aid Society on Monday, January 17.

National and international newspapers quickly picked up the story and put a “surprised and astounded” Mrs. Vawters  on the defensive. In 1949, Washington D.C.’s population hovered around 800,0006 and the poverty rate among the capital’s children stood at 47.6%. Yet in the eyes of the American press, the problem was not child poverty and cold children but the projection of an unfavorable international image during the Cold War. Press reaction ranged from bemused to outright hostile.

on the defensive. In 1949, Washington D.C.’s population hovered around 800,0006 and the poverty rate among the capital’s children stood at 47.6%. Yet in the eyes of the American press, the problem was not child poverty and cold children but the projection of an unfavorable international image during the Cold War. Press reaction ranged from bemused to outright hostile.

“The Agence France Presse described ‘a situation that could be called almost annoying due to the confusion caused by the unexpected news’ of the donation. There was no intention to demonstrate that in a rich country like the United States, there are ‘poor’ children, added the AFP.”7

“Grateful for a Gift from Argentina” Pictures from Argentina Monthly Magazine, April 1949. Mrs. Fay Vawters is on right.

On Monday, January 17 the Pittsburg Post-Gazette headlined,

“Foreign Aid of America!

Eva Perón Sends Clothes,

Donation for 600 Washington Children Proves Embarrassing for Charity Society.”

“The usual flow of relief assistance from the United States to the needy abroad will be reversed here Monday, to the astonishment of the Children’s Aid Society of Washington, where the Argentine embassy delivers clothing sent by Mrs. Juan D. Perón, wife of the president of Argentina for 600 American children. “Word of the windfall was brought to the Society here on Thursday, it was disclosed Sunday, by Agustín Américo Merlo, third secretary of the Argentine embassy. Now the Reverend and Mrs. Ralph E. Vawters, who operate the society, are trying to figure out whether it is good or bad.

“The usual flow of relief assistance from the United States to the needy abroad will be reversed here Monday, to the astonishment of the Children’s Aid Society of Washington, where the Argentine embassy delivers clothing sent by Mrs. Juan D. Perón, wife of the president of Argentina for 600 American children. “Word of the windfall was brought to the Society here on Thursday, it was disclosed Sunday, by Agustín Américo Merlo, third secretary of the Argentine embassy. Now the Reverend and Mrs. Ralph E. Vawters, who operate the society, are trying to figure out whether it is good or bad.

“ ‘We really don’t know,’ Mrs. Vawters said. ‘All I know is that we are startled, shocked dumbfounded and at a loss for adjectives adequate to describe our quandary.’

...

“Mrs. Vawters is very appreciative, she made clear, but a little concerned lest it be thought that she had asked for foreign help. And if Moscow picks up the story and capitalizes on it to prove that the US has slipped into a terrible depression and needs help from abroad, Mrs. Vawters will be mortified.”8

The donation made page one of the Miami Daily News.

Eva Perón Foundation Forwards Gift

Argentina to Clothe Washington’s Poor

“Surprise mingled with embarrassment today at the news that the María Eva Duarte de Perón Social Assistance Foundation of Argentina is donating clothes to care for 600 needy Washington children.

“Embarrassment was the reaction among State Department officials. The officials were obviously concerned over the Argentine gift which seemed to imply that the United States is unable to look after its own needy.

“There was some apprehension as to what use Russia might make of the matter in view of the Moscow propaganda line that Americans live in pretty miserable conditions compared to those of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

“Mrs. Vawters operates the society with her husband, the Reverend Ralph Vawters. It normally clothes about 1,000 children a year.”9

In a followup story on January 18, the Pittsburg Post-Gazette headlined

Foreign Aid for America!

Eva Perón Sends Clothes-Donation

Argentina Helps Our Kids, Some of Us Don’t Like It

Capital Charity Group Extends Thanks

Board Member Quits, Contributors Irked

Wash. Jan. 17 (AP)

“A Washington children’s charity Monday accepted from Argentine embassy officials a half dozen crates of children’s clothing with warm thanks to Señora Perón.

“The clothing was donated by an Argentine foundation headed by the wife of President Perón.

“The Reverend Ralph Vawters, president of the charity organization gave Argentine officials a letter expressing warm thanks to Señora Perón ‘for her gracious gift.’ “The charity officials were a bit upset at first when, in response to an inquiry sent to all embassies here for small money donations, the Argentines sent word of a shipment of clothing for 500 kids.

“ ‘We called the State Department to see if we should accept all that clothing,’ Reverend Vawters told newsmen. ‘They said they didn’t see any reason why we shouldn’t accept. So we did.’

“ ‘I hope we didn’t do anything wrong, accepting this for the kids.’

“Distribution of the clothing to children in Washington slum areas will start Saturday. “The Reverend Vawters said a number of his regular contributors have served notice, because of acceptance of the gift from the Argentine foundation. They will no longer make contributions. And a member of his advisory board resigned.”

TIME

Monday, January 24, 1949

“Helping Hand”

Time10 implied that Evita sent the clothing because “it would be fun to play the role of Lady Bountiful.” But no one who knew Evita would ever accuse her of associating poverty with fun. As First Lady she stayed at the Ministry of Labor until three or four o’clock in the morning so that no one in need would be sent home without seeing her. She fearlessly kissed lepers. And she never forgot the sacrifices her own mother had made so that her five children would not go hungry. Poverty was never fun for Evita.

The most hostile reaction came from the Pittsburg Press. The paper scolded the Vawters for providing the Soviets with a possible propaganda coup by calling attention to the poverty in the nation’s capital, called the Peronista government a “dictatorship,” questioned the legitimacy of the Vawters’ society (outside the umbrella of the Community Chest) and doubted that the children were really “needy.”

The Pittsburg Press

January 18, 1949

We Asked For It

“There is said to be some red faces among Washington officials because the Eva Duarte de Perón assistance Foundation of Argentina is donating clothing for 500 ‘needy’ Washington children.

“The strange situation, which the Perón dictatorship in Argentina will make the most of, came about in this form.

“The Children’s Aid Society of Washington, a private non-Community Chest organization, solicited an official of the Argentine embassy for a donation. He forwarded the letter to the photogenic wife of Argentina’s president.

“This is not, it should be said, an organization which deals in small change or hides its light under a bushel.

....

“Belatedly, Mrs. Ralph Vawters, who operates the Children’s Aid Society in Washington, professes to be ‘astounded’ by the size of the gift and protests that she did not know the Perón foundation was being solicited.

“It can be expected that the Moscow propagandists will leap on this story as an additional evidence to prove that Americans live under miserable conditions and must seek help from foreigners because the ‘Wall Street capitalists’ grab everything in sight.

“Such misadventures will happen when American citizens in their zeal for solicitations go so far afield as to involve officials of another nation in our domestic concerns.

“There ought to be red faces all over the place.

“If we cannot care for our own without asking members of foreign legations for donations, we deserve to be embarrassed.”11

The State Department decided to cut the Soviets off at the pass.

“The Voice of America, the State Department’s foreign broadcasting service, broadcast a factual report on the gift right after it was made known Saturday.”12

Fortunately for the children, Evita’s generosity (and willingness to ruffle feathers) as well as Fay Vawter’s common sense prevailed.

Refusing to be intimidated, Mrs. Vawters had the last word. “Where the clothing comes from makes no difference to the kids. They need it.”13

Argentina

April 1, 1949

“Grateful for a Gift”14

In the turgid prose of the times, the monthly magazine Argentina reported on Eva Perón’s donation to the children of Washington.

The pictures accompanying this article are taken from Argentina.

“If one is guided by most people’s reactions, the donation that the Fundación de Ayuda Social María Eva Duarte de Perón made to the Children’s Aid Society was very well received. Soon after finding out about the donation, people in the street agreed: they approved the donation and disapproved the obstructionist interpretations that appeared in the press. The donation was big news, peaceful news in the midst of a multitude of worrisome information.

“Even those who did not see the necessity of receiving aid from abroad to help the local poor enjoyed the spectacle of an international event that occurred outside the usual diplomatic channels, channels that for a long time had not produced even one pleasing note, probably because of circumstances although a lack of vision may also be blamed.”15

“Grateful for a Gift” went on to say that, in response to commentaries in the press, the Argentine embassy sent a note to the State Department stating that the Fundación Eva Perón had donated the clothes and shoes as a normal act of good will from which no complicated conclusions should be drawn-as some members of the press were doing. The State Department agreed and labeled the donation a “well-intentioned gesture.” Within the diplomatic sphere, in the sphere of “what will the Russians, the other countries, the ministers, the Congress, the papers say?” the matter was quickly closed without hitting any stumbling blocks.

The Argentina article reported the American people are not imperialistic and neither are most politicians and newspapers although the papers are often subordinated to economic interests. However, the public is not interested in interpretations of the news that have been strained through filters. In this case, a way had been found to elude the nets.

Argentina also reported that the embassy had received numerous letters from different regions of the United States, all thanking the Señora Eva Perón for a generosity that the American papers had refused to recognize. The letter writers were glad that she had found a way to get around the roadblocks imposed by “self-important showoffs who paint things as they wish others to see them”.

“A remarkable city, Washington: it combines Northern charm and Southern efficiency.”16)

It still contains a high rate of child poverty. D.C.’s 19.9 % poverty rate in 2010 made it third-highest in the nation, after Mississippi and Louisiana.17

During the Depression and the Cold War, America’s First Ladies acted to alleviate poverty without concerning themselves about what the Russians would think. When Franklin Roosevelt was Assistant Navy Secretary, his wife Eleanor joined First Lady Ellen Wilson in touring the capital city’s slums, home to a largely African-American population. A congressional bill mandated the destruction of the dangerous and unsanitary buildings but World War II interrupted relocation efforts.18

Eleanor Roosevelt believed that universal human rights begin “in places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination.” Courageous Eleanor, the first white District of Columbia woman to respond to NAACP and the Urban League membership drives, fought for equal rights throughout FDR’s four terms in the White House. Far from denying the existence of poverty in the United States, Eleanor worked to establish a model community in Appalachia in 1937, east of Morgantown, West Virginia: Arthurdale, “the subsistence homestead community closest to her heart.”19

Jacqueline Kennedy never forgot the kindness-and the destitution-she saw in Appalachia. “The people were so friendly. There could be a mother ... nursing a baby on a rotting front porch, but she’d smile and say, ‘Won’t you come in?’ ”20 In 1961, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy commissioned the West Virginia’s Morgantown Glassware Guild to produce the White House crystal, benefitting the state’s economy and inspiring Americans to buy the “President’s House” crystal for their own homes.21 Like Mrs. Roosevelt, she saw the effects of poverty when she visited homeless children in Washington, D.C.22

As First Lady, Mrs. Kennedy also gave gifts to children in other countries. In 1962 she brought the children of India “a portable American classroom equipped with art materials, known as the Children’s Carnival of the Arts.”23

Surely these two remarkable First Ladies would have welcomed Evita’s donation without denying that poverty existed in D.C., denigrating Mrs. Vawters or accusing her of fueling Russian propaganda.

On January 20, 1949, Harry Truman took the oath of office of President of the United States with his hand placed on two Bibles: the Bible first used at his swearing-in after President Roosevelt’s sudden death on April 12, 1945 (open to the Beatitudes) and a Gutenberg Bible (open to the Ten Commandments). In his inaugural address, Truman stated: “More than half the people of the world are living in conditions approaching misery. Their food is inadequate. They are victims of disease. Their economic life is primitive and stagnant. Their poverty is a handicap and a threat both to them and to more prosperous areas.”

In 1949, poverty lay at the doorstep of the White House. Almost half the children in Washington (over 47%), many of them African Americans, were poor. Truman outlined his program for peace and freedom minutes after his hand had rested on two texts with clear messages: charity begins at home.

In 2002, the Argentine ambassador in Washington, Diego Guelar, asked the city of Washington to honor Evita’s concern for the District’s poor children by naming a public space for her.24

In 2002, the Argentine ambassador in Washington, Diego Guelar, asked the city of Washington to honor Evita’s concern for the District’s poor children by naming a public space for her.24

In life, Evita had never requested recognition from Washington. She knew that the action mattered, not the name attached to it. She told her sister, as one of her works was being inaugurated, “I leave them the easiest task-that of changing the names.” Sadly, her premonition came true. After the 1955 coup d’état, the military did destroy or rename what the Foundation had constructed. Yet they could not destroy Evita’s place in her people’s affection or in her country’s history. She has never needed monuments in public places to be remembered.

“Eva Perón Foundation Forwards Gift / Argentina to Clothe Washington Poor,” Miami Daily News, January 15, 1949, p.1.

During the first Peronista government (1946-1955), labor attachés, agregados obreros (and some women agregadas), were added to Argentine embassy staffs with mixed results. The labor attachés’ job was to contact the host country’s labor unions and leaders. They had little or no contact with the military or commercial attachés. In their eagerness to please Perón, labor attachés often included in their reports information that the Embassy had withheld, thus making themselves a thorn in the side of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It is doubtful that Evita read any of their reports. For more information on agregados obreros, see Memorias de un Ciudadano Ilustre by Jorge Ochoa de Eguileor, INIHEP (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Históricas Eva Perón), 2007, pgs. 43-48.

Miami Daily News, op.cit.

The Fundación sent aid and medical personnel to many countries, including Bolivia, Uruguay Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Honduras, Paraguay, Austria, Spain, France, Israel, Italy, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Ireland, Portugal, Germany, Turkey, Czechoslovakia, England, Holland, El Salvador, Philippines, Peru, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Syria, Norway, and the United States. See Néstor Ferioli’s La Fundación Eva Perón / 2 (Buenos Aires, Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990), pgs. 113-115, for details. Some countries received aid throughout the life of the Fundación.

From the Alberto Casares Collection, quoted in communicacionpopular.com.ar/el-día-que-eva-peronayudo- a-los-ninos-pobres-y-negros-de-washington/

1950 census

communicacionpopular.com.ar/el-día-que-eva-peron-ayudo-a-los-ninos-pobres-y-negros-de-washington/

“Foreign Aid for America!” Eva Perón Sends Clothes. Donation for 600 Washington Children Proves Embarrassing for Charity Society,” Pittsburg Post-Gazette, January 17, 1949, p.4.

“Eva Perón Foundation Forwards Gift,” op.cit.

“Helping Hand,” Time, Monday, January 24, 1949, online.

“We Asked For It,” Pittsburg Press, January 18, 1949, p.12.

“Argentina Helps Our Kids, Some of Us Don’t Like It,” Pittsburg Post-Gazette, January 19, 1949, p.4.

Ibid.

Alberto Caprile, Jr., “Se agradece un regalo argentino,” Argentina Monthly Magazine, April 1, 1949, 57-59.

Steven F. White, “De Gasperi through American Eyes: Media and Public Opinion 1945-53,” Italian Politics and Society, Fall/Winter 2005, 11 (online).

““The father of a Congressional Medal of Honor winner who was in Washington at the invitation of the President, was ordered out of the dining room of a capital hotel because he wasn’t wearing a coat. A Washington columnist reported having overheard, ‘A remarkable city, Washington: it combines Northern charm and Southern efficiency.’ ’’ Quoted in It Happened in 1945 by Clark Kinnaird (New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1946), 348. President Kennedy also called Washington a city of Southern efficiency and Northern charm.

www.tbd.com.articles/2011/09/d-c-poverty-rate-is-third-highest-in-the-nation-says-u-s-census-66525.htm

www.firstladies.org/biographies

“Attack at Arthurdale,” Time, June 6,1938 (online).

Jacqueline Kennedy, Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy (New York: Hyperion, 2011), 67.

Leticia Baldrige and René Verdon, In the Kennedy Style (New York: Doubleday, 1998),62.

On December 13, 1962, for example, Mrs. Kennedy visited the Junior Village, an institution for homeless children in Washington. See Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years (New York: Little, Brown & Company, 2001), 136.

In those long ago days (1962) when an American First Lady could wave to cheering crowds as she stood next to the President of Pakistan in an open car and be greeted by tribesmen bearing gifts when visiting Peshawar and the Khyber Pass. See Mrs. Kennedy and Me by Clint Hill with Lisa McCubbin (New York: Gallery Books, New York, 2012, 131).

Diego Guelar visited the mayor of Washington, Anthony Williams, to ask that Evita be honored by naming a public space after her. Williams said he like the idea, and he would bring the proposal before the Council of the District of Colombia. In a letter to Williams, the ambassador wrote that Argentina was going through very difficult times and a gesture of appreciation for the concern and affection Eva Perón had shown for the needy children of Washington would be greatly appreciated: “Nothing would be more comforting that that a public space in Washington receive the name of this extraordinary woman.” “Piden reconocimiento para Evita”

Clarín.com/diario/2002/05/06 online