From Beneficence to Social Justice

In

order to understand the social action undertaken by Evita within the framework

of Perón's first presidential term and especially with reference to the

Fundación Eva Perón, it is necessary to understand the meaning of the

revolution in social policy inserted "into the tendency of the governments

which sprang from the June 4, 1943 Revolution to modernize, restructure

and amplify the state apparatus, establishing a greater control over some

institutions and putting into practice a social policy essentially opposed

to that which had existed until that moment." (1) In

order to understand the social action undertaken by Evita within the framework

of Perón's first presidential term and especially with reference to the

Fundación Eva Perón, it is necessary to understand the meaning of the

revolution in social policy inserted "into the tendency of the governments

which sprang from the June 4, 1943 Revolution to modernize, restructure

and amplify the state apparatus, establishing a greater control over some

institutions and putting into practice a social policy essentially opposed

to that which had existed until that moment." (1)

The era of Argentine social policy which Perón

initiated from the Secretaría de Trabajo y Previsión and which later marked

his Presidency remained forever linked to Evita.

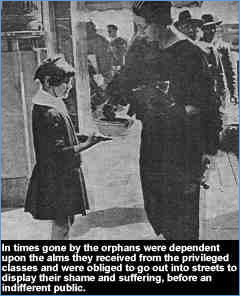

The fact that the First Lady made an incursion

into the realm of "social welfare" should not surprise anyone. All first

ladies had done so.

Men considered this a privileged way in which

women could manifest "the lovely qualities which the beautiful sex [women]

possess to a high degree" ; the institutions within this orbit were entrusted

from the beginning to the high society ladies of Buenos Aires.

The primordial objective which guided the government

at that time - "moral perfection and the cultivation of the spirit in

the beautiful sex and the dedication of that same sex to what is called

industry" (2)

The trajectory of this institution, which was

funded by donations, state subsidies (3) (*1),

collections and social events, was not exempt from social conflicts with

its employees who received very small wages and whose right to days off

was not respected. (4)

This matter was taken under consideration just

after Peronismo came into power. On June 14, 1946, 200 employees of the

Society of Beneficence signed a petition in which they made their situation

known. A few days later, the matter was brought up in the Senate, where

Senator Diego Luis Molinari introduced a request for intervention, transmitted

to the Executive Branch on July 25.

As Marysa Navarro has stated very well, "all of these

institutions were adequate for prePeronista Argentina, but were an anachronism,

a profound contradiction to the society being gestated after Perón assumed

the presidency." (5)

Therefore,

Degree 9414/46 declared that the Society of Beneficence of the Capital

was to be intervened "so as to restructure its organization and adjust

its function towards the technical norms and principles of assistance

and social welfare inspired by government policy" ; Dr. Armando Méndez

San Martín was designated auditor. Therefore,

Degree 9414/46 declared that the Society of Beneficence of the Capital

was to be intervened "so as to restructure its organization and adjust

its function towards the technical norms and principles of assistance

and social welfare inspired by government policy" ; Dr. Armando Méndez

San Martín was designated auditor.

The opposition connected the intervention to Eva

Perón, whom they believed to be angry because the Society ladies had rejected

her; she was seen as the deciding factor in the executive decision. Mary

Main's story,(*2) which

has been profusely repeated and is the basis of much literature, is an

example of this version:

"It was customary for the wife of the President to become

the honorary president of the Benevolent Society.

"When Perón was inaugurated the good ladies were in

a dilemma. They could not possibly invite "that woman" to be president

of their society. It would mean establishing some sort of social contact

with her and, really, she was the sort of person who should have been

at the receiving end of charity! It was unthinkable, so they made no move.

"But Eva was not the one to allow herself to be

passed over so easily. She sent to inquire why they had not come to offer

her the presidency of their society. With their unfailing urbanity they

replied that she was, alas! too young, that their organization was one

which must be headed by a woman of maturity.

"Eva at once proposed that they should make her mother,

Doña Juana, president - a suggestion that almost makes one credit her

with a sense of humor.

.....

"This rebuff had consequences which these ladies, who had for so long

occupied an impregnable position, could not possibly have foreseen. Eva

set out to destroy both them and their Society, and out of this fury of

destruction there rose the plan for her own charitable organization...

." (6)

Argentine historian Fermín Chávez relates the

following anecdote told by Dr. Esteban Rey: "As is known, there was a

conflict which became public and which culminated with the intervention

of the Society by the Peronista government. Dr. Leloir, who was a relative

of the last president of the Society, echoed the worry the ladies had

in the sense of not having their reputations besmirched in the eyes of

posterity by what was  being

said about them. Therefore, he was the bearer of an invitation to Evita

(and was invited to accompany her) to visit his relative. At first the

meeting was very tense, but as tea was being served, Evita's joviality

and charm won over the ladies... . The president, after having expressed

her satisfaction at the way the meeting was going, said to her, "Señora,

we have decided that from now on we will support your work, and to start

off, we have just programmed a bridge party at the Plaza [Hotel] ... ."

She could not finish her sentence. Evita stood up and said brusquely,

"Absolutely not! You must realize that in this country the sorrows of

the poor will never again serve as entertainment for the rich. Good day,

ladies!" (7) being

said about them. Therefore, he was the bearer of an invitation to Evita

(and was invited to accompany her) to visit his relative. At first the

meeting was very tense, but as tea was being served, Evita's joviality

and charm won over the ladies... . The president, after having expressed

her satisfaction at the way the meeting was going, said to her, "Señora,

we have decided that from now on we will support your work, and to start

off, we have just programmed a bridge party at the Plaza [Hotel] ... ."

She could not finish her sentence. Evita stood up and said brusquely,

"Absolutely not! You must realize that in this country the sorrows of

the poor will never again serve as entertainment for the rich. Good day,

ladies!" (7)

To

be strictly truthful, the fate of this traditional institution had been

conceptually sealed since 1943, that is to say much before Evita could

have had any influence. Beneficence, as it was understood and practiced

until then in our country, was over; it would give way to social justice.

"...Perón has taught me," Eva would say in My

Mission in Life, "that what I do for the humble of my country is nothing

more than justice.

"...It is not philanthropy, nor is it charity,

nor is it alms, nor is it social solidarity, nor is it benevolence. It

is not even social welfare, although, to give it a more nearly appropriate

name I have called it so.

"To me it is strict justice. What made me

most indignant when I commenced it was having it classified as "alms"

or "benevolence."

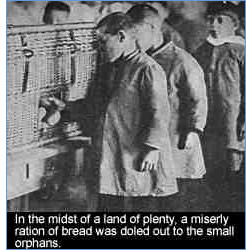

"For alms, as far as I am concerned, was always

a pleasure of the rich: the soulless pleasure of exciting the desires

of the poor without ever satisfying them. And so that alms should be even

meaner and crueler, they invented "benevolence" and so added to the perverse

pleasure of giving alms the pleasure of enjoying themselves happily with

the pretext of the hunger of the poor. Alms and benevolence, to me, are

an ostentation of riches and power to humiliate the humble.

I think that God must often be ashamed of what

the poor receive in His name!" (8)

The Task

Begins

"Before

starting on the subject," Eva Peron would say in My Mission in Life,

"it is well to remember that Perón is not only President of the Republic;

he is also the Leader of his people.

"This is a fundamental condition, and is directly

related to my decision to handle the role of wife of the President of

the Republic in a manner different from any President's wife who had preceded

me.

...

"I

had to have a double personality to correspond with Perón's double

personality. One, Eva Perón, wife of the President of the Republic,

whose work is simple and agreeable, a holiday job of receiving honors,

of gala performances; the other, "Evita," wife of the Leader

of a people who have placed all their faith in him, all their hope and

all their love." (9) "I

had to have a double personality to correspond with Perón's double

personality. One, Eva Perón, wife of the President of the Republic,

whose work is simple and agreeable, a holiday job of receiving honors,

of gala performances; the other, "Evita," wife of the Leader

of a people who have placed all their faith in him, all their hope and

all their love." (9)

With this conviction, Evita began to develop her

activity as a bridge between Perón and his people immediately after Perón's

inauguration on June 4, 1946. She interceded in favor of the workers,

visited marginalized neighborhoods, distributed clothes and food to needy

families, solved problems which people told her about in letters which

they sent to the Presidential Residence and attended to people who came

to the door.

Even though she had some idea of the difficulty

of the endeavor even before she began to undertake it, it was only after

she had begun that she realized the magnitude of her task.But by then

she had deleted from her dictionary the word "impossible." (10)

"At first I attended to everything personally.

Then I had to ask for help. Finally I was obligated to organize the work

which in just a few weeks had become extraordinary." (11)

From the beginning Evita counted on the help of

the Residence employees. Atilio Renzi, in charge of Residence personnel,

would become her right hand.

One of the garages was converted into a storehouse.

"When Eva Perón returned from a trip to the Province of Santa Fe," he

remembered, "she became enthused with the idea of creating a great social

help organization. And when the labor unions began to send her donations

(sugar from the people of Tucumán; clothes and material from the textile

unions; leather and shoes from the leather workers union), we had to find

a place to store everything: an old unused garage. The cook, Bartolo,

the waiters, Sánchez and Fernández, the maid Irma and I baptized the place

"The Delightful Store, La Tienda de las Delicias." (*3)

After Perón had gone to bed, we would stay up

with Eva until dawn to package the merchandise. The sugar was our biggest

problem: in her enthusiasm, la Señora [Evita] spilled more on the floor

than she packaged into paper bags." (12)

In September, Evita began work in what had been

the Secretaría de Trabajo y Previsón, in the same office where Perón had

worked from 1943 to 1945, a highly symbolic act as she herself manifests

in her autobiography.

The multiplicity, diversity and urgency of the

matters brought before her caused her working day to lengthen each day

more.

.....

A little later, the until then titled "Social

Help Crusade" or "María Eva Duarte de Perón Social Work" would give way

to the "María Eva Duarte de Perón Social Work Foundation" as a consequence

of the amplitude with which Evita's activities in society had increased

and of the necessity of establishing a legally constituted organism which

could centralize and control these activities. (13)

La Fundación Eva Perón

The

María Eva Duarte Social Help Foundation was established on June 19, 1948.

Degree number 220.564 on July 8, 1948, gave it legal jurisdiction and

approved its Statutes. |

(*1) Translator's note: In 1939 the Congressional Representative Juan Antonio

Solari told about Society employees who routinely worked 12 to 14 hur

days with a day off only every 10 to 15 days and were paid from 45 to

90 pesos when a fair minimum wage was considered to be 120 pesos. See

Diario de Sesiones, 1939, vol. 7.

(*2) Translator's note: Mary Main's biography of Evita has no footnotes, no

bibliography, no documentation of any sources or references; however,

it is often cited and is the basis of the opera Evita.

(*3) For another version of how "Las Delicias" got its name, see the Mundo

Peronista article. Click here

Bibliography

Borroni, Otelo, and

Roberto Vacca. La Vida de Eva Perón. Buenos Aires: Galerna, 1971.

Chávez, Fermín. Eva Perón Sin Mitos. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Theoría,

1996.

Ferioli, Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor

de América Latina, 1990.

Main, Mary. The Woman With the Whip. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company,

1980.

Navarro, Marysa. Evita. Buenos Aires: Planeta, 1994.

Perón, Eva. My Mission in Life. Translated by Ethel Cherry, New

York: Vantage Press, 1953.

|