To Be Evita ©

- Part II

The

Day Which Split History: October 17, 1945

In 1943 the separation between the

real country and the government dominated by the oligarchy was a flagrant

one. The climate became more tense as the time for elections drew near.

With the increased tension came the foreboding that the regimen would

put its fraudulent seal on these elections just as it had on previous

ones. On June 4, 1943, a military coup ousted President Ramón Castillo.

When General Pedro P. Ramirez assumed

the Presidency, Colonel

Juan Perón, unknown to the citizenry but prestigious among

his military colleagues, took over the National Department of Labor. One

month later the Department was transformed into the Secretariat of Labor

and Social Welfare. Here Perón laid the political groundwork which would affect the next decade of Argentine

history.

A real national tragedy would now

join two people who up to this moment had been ignorant of each other's

existence.

On January 15, 1944, an earthquake

destroyed 90% of the Andean city of San Juan. Seven thousand people died

and 12,000 were left injured. From the Secretariat of Labor and Social

Welfare, Perón organized a national relief effort and invited the

most popular stars of the day to participate. Eva Duarte was among them

and helped take up collections for the needy.

On January 22, a great festival

was held at Luna Park Stadium with all benefits destined for the victims

of the earthquake. Eva Duarte and Colonel Perón began a relationship

which would be socially confirmed at a gala held at the Colón Opera

House on July 9 to celebrate Argentina's Independence Day.

Two days before, General Farrell

(who assumed the Presidency on March 11 when Ramirez resigned) had designated

Perón as Vice President. Perón retained his first position

in charge of the Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare as well as a

second position which he had recently assumed as Minister of War.

Eva, for her part, had three programs

on Radio Belgrano: at 10:30 A.M. she starred in "Towards a Better Future"

which exalted the goals of the 1943 Revolution; at 6:00 P.M. she was in

charge of the cast of the drama, "Tempest," and at 10:30 P.M. she starred

in "Queen of Kings.

On May 6, 1944, she was chosen President

of the Agrupación Radial Argentina, a union entity which she had

founded in 1943.

Perón had become the key

figure in the new military government-and the most irritating as far as

the opposition was concerned. Eva's presence and the place Perón

accorded her presented another target; this time his own colleagues would

take aim at it. If Perón was atypical, the woman at his side was

even more so: she had decided to stand at the side of her man, not behind

him. And Perón had accepted that which was unacceptable at the

time.

On October 13, 1945, one sector

of the government was successful in obtaining Perón's resignation

from all his positions. He was detained and sent to Martin Garcia, an

island off the coast of Buenos Aires. By this time the workers had realized

that Perón's disappearance would mean the disappearance of his

labor policy and all the conquests they had made. At dawn on October 17

they began to abandon their workplaces and head towards Plaza de Mayo:

they demanded the appearance of their Colonel. Perón's withdrawal

had produced a vacuum of power which only he could fill.

That night Perón appeared

on the balcony of the Casa Rosada and announced that elections would be

held soon. The Plaza became a witness to a new political force in Argentina.

For the cheering occupants of the overflowing Plaza de Mayo, Perón

was now not only their leader but also their candidate.

As far as Eva's role in the crisis

of October 17, at this stage of our investigative research, we have only

the testimony of witnesses. Some have her fighting elbow to elbow with

the workers (Alberto Mello), weaving together the threads of the movement,

bringing the people to the Plaza and on the 17th placing herself at the

vanguard of the movement (Perón), playing no part at all in the

mobilization of the workers (Cipriano Reyes), or totally absent from all

the events (Luis Monzalvo).

In the light of what we know about

Eva's personality at the time and from what she showed herself to be in

later years, it is difficult to validate the opinion of those who sustain

that she did not participate at all in the events. At the same time, the

position she occupied at Perón's side, with the knowledge of what

mechanisms it was necessary to activate but not yet with the power and

influence to activate them makes it difficult to sustain that she was

the pivot of these foundational events of the Peronista Movement. Perhaps

Eva was situated between the two extremes: she could seek a habeas corpus,

open contact with those she knew she could count on and who would be able

to mobilize people, and participate in the events to the extent her resources

would permit.

Eva never claimed for herself the

role of leader on that 17th of October: Perón was won back by the

people.

"That week of October, 1945, is

a week of many shadows and of many lights. It would be better if we did

not come too close.., we should look at it again from farther away. However,

this does not impede me from saying, with absolute frankness and in anticipation

of what I will someday write in more detail, that the light came only

from the people" (Eva Perón, op.cit., p.39).

October 17th confirmed for Eva that

the events of the past few days did not portend an end (as some had wished)

but a new beginning in Argentine history. This new beginning would have

as its foundation the relationship between a man, Perón, and the

bases of his support, the workers - the descamisados (the shirtless ones).

This relationship withstood all attempts to destroy it and lasted until

Perón's death in 1974. It brought him to the Presidency of Argentina

in 1946, in 1952, and in 1973, after eighteen years in exile.

Perón wrote two letters to

Eva from his prison on the island of Martin Garcia. In one of them he

said, "Today I have written to Farrell, asking him to accelerate my retirement:

as soon as I get out of here we'll get married and we'll go someplace

where we can live in peace.

Their civil marriage took place

on October 22 and the religious ceremony on December 10, the time when

they could go somewhere and live in peace never came.

The Labor Party chose Perón

as its presidential candidate and Quijano as vice president. The opposition,

united under the name of Democratic Union, chose Tamborini and Mosca as

its candidates. Elections would be held in February of 1946.

The campaign was giddy, violent,

aggressive-as are so many in Argentina-in word and in deed (it was marred

by sabotage).

"Dairy farm [tambo], urine, and

flies ["mosca" means fly in Spanish]... the formula for manure," said

one side.

"Greasy blacks without any conscience,

dirty feet," countered the other.

By the end of December the political

campaigns were ready to hit the interior of the country. "El Descamisado,"

the Labor Party's campaign train, came and went along the tracks. For

the first time in history, a candidate's wife accompanied him. At each

campaign stop, she handed out buttons and greeted the people personally.

We begin to see the profile of another

woman: Eva has definitely entered into the political arena. On February

8 she took another step forward: a convocation of working women met at

Luna Park to show their adhesion to the Labor Party ticket. The presidential

candidate was ill and could not go. Eva went in his place. It was her

debut as a speaker- but they wouldn't let her speak. Every time she tried,

the women shouted, "We want Perón!"

A few months later she would be

acclaimed. She would have become another person. She would be EVITA.

1945-1952

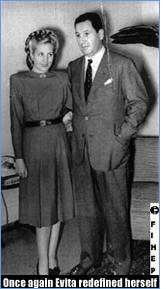

When

Perón assumed the Presidency, Evita, unlike other Presidents' wives,

asked herself what role she would assume from then on. Once again she

questioned herself about herself, she redefined herself. This time her

role would be defined by her relationship to Perón as President

and Leader.

When

Perón assumed the Presidency, Evita, unlike other Presidents' wives,

asked herself what role she would assume from then on. Once again she

questioned herself about herself, she redefined herself. This time her

role would be defined by her relationship to Perón as President

and Leader.

"This is a foundational circumstance

and is related directly to my decision to be a President's wife who does

not follow the old model. I could have followed those models. I want to

make this clear because sometimes people have tried to explain my "incomprehensible

sacrifice" by arguing that the salons of the oligarchy would have been

closed to me in any case. Nothing is further from the truth nor from common

sense. I could have been a President's wife in the same way that others

were. It is a simple and agreeable role: appear on holidays, receive honors,

"dress up" and follow protocol which is almost what I did before, and

I believe more or less well, in the theater and the cinema. As far as

the hostility of the oligarchs goes, I can't help but smile. And I ask:

why would the oligarchs reject me? Because of my humble origins? Because

of my career as an actress? But has that class of persons ever taken those

reasons into account, here or in any part of the world, when it is the

case of the wife of the President? The oligarchy was never hostile to

anyone who could be useful. Power and money are never bad advantages for

a genuine oligarch... . But I was not just the spouse of the President

of the Republic, I was also the wife of the leader of the Argentine people.

"Peron had a double personality

and I would need to have one also: I am Eva Peron, the wife of the President,

whose work is simple and agreeable ... and I am also Evita, the wife of

the leader of a people who have deposited in him all their faith, hope

and love.

"A few days of the year I represent

Eva Perón ... "

"Most of the time, however, I am

Evita ... "

We do not need to speak of Eva Perón.

What she does appears profusely in newspapers and magazines everywhere.

"On the other hand, I would like

very much to talk about Evita... ." (Perón, Eva: op cit. pgs. 69-71).

Strangely enough, when the historical

figure of Evita is discussed, people seem to be most interested in delving

into other instances of her life: her childhood, her family, the life

of her parents, the circumstances surrounding her decision to leave home,

her personal life in Buenos Aires, her success as an actress, the beginning

years of her relationship with Perón, the reasons for her actions.

However, if she had not made the decision to "be Evita," we Argentines

would not even be aware of her name, as we are unaware of the names of

so many other first ladies.

Therefore, it is very interesting

to talk about Evita, interesting to talk about her work with the disadvantaged,

the working class, with women, all woven together into the fabric of her

unceasing activity.

After Perón became President,

Evita went to work on the fourth floor of the Central Post and Telecommunications

office where she began to attend to delegations of workers who asked her

to intervene in solving labor disputes or helping them obtain better wages.

This relationship with the unions continued to intensify until 1952. It

provided her with a solid political power base and created a foundation

for her social work. She also began to receive the needy and to take care

of their emergencies. She supported the government's policies, and she

paid special attention to a sector which had not been taken into consideration

before. On July 25th she spoke to the women of Argentina, and announced

new measures designed to curb speculation. Beginning in October, her visits

to factories increased and her trips to poor neighborhoods put her in

contact with the people and their needs.

She found much to do. "And we began,"

she said in The Reason for My Life. "Little by little. I couldn't

tell you on what exact day. I can tell you that at first I took care of

everything myself. Then I had to ask for help. Finally I had to organize

the work which in just a few weeks had become extraordinary." (Perón,

Eva: op. cit. pg. 134).

On September 24th Evita began working

from Perón's office in the Secretariat of Labor and Welfare. "I

went to the Secretaría de Trabajo and Previsión because

there I could meet my people easily and without problems; because the

Minister of Labor and Social Welfare is a worker and he and Evita understand

each other without any bureaucratic runarounds; and because the Secretaría

offered me the tools I needed to begin my work... The functionaries of

the Ministry collaborate with me in finding a solution to the problems

brought by the unions, gathering background information, examining the

solution on its own merits as well as studying the possible social and

economic repercussions." (ibid, pgs. 83-84)

The Secretaría was a symbolic

place. On July 30, in one of the meat packing plants at Parque de los

Patricios, Evita said, "My mission is to transmit to the Colonel the concerns

of the Argentine people." Evita saw herself as "the bridge" which brought

Perón nearer to his people. She would become more than that; as

the years went by, her activity became more intense and her working days

interminable.

She began her mornings by receiving

the people with the most urgent needs at the Residence, then going to

the Secretaría to meet with the unions and the poor. If she had

to interrupt her interviews because of an official reception, homage,

visit or any other activity involving protocol, the people left waiting

at the Secretaría would stay until she returned. And she always would return and would not leave until everyone had been taken

care of. Her days were divided into two parts-- mornings and afternoons

one could say, with a light lunch at 2:00, 3:00 or even 6:00 P.M.

On Wednesdays the unions visited

Perón, and Evita would usher the members in to see him. However,

she rarely participated in these meetings. She continued to work at her

own affairs in a nearby office.

Evita had the habit of dropping

by unexpectedly to visit the Foundation's works under construction and

on Thursdays she would visit its establishments around greater Buenos

Aires.

In 1947 she was leaving the Secretaría

around 10:00 P.M. and as the years went by her working day grew longer.

The daily paper Democracia described one day, Friday, May 19, 1950:

"She starts her morning very early

in her office at Trabajo y Previsión and the first part of her

day lasts until 4:00 P.M. At 5:00 P.M. she's back and continues to work

until dawn with only a few short breaks. One break is around 8:30 when

she and General Perón attend the signing of a contract which benefits

the alimentation (food) workers. Another is around 11:00 P.M. when she

attends the homage the railroad workers pay to one of their leaders who

has been named a board member of the National Railways. From there she

goes to a banquet at Retiro Park where she is fervently cheered by the

workers of the bottled water industry. Once back at Trabajo y Previsión,

she presides over an act organized by the workers of the cooking oil industry."

Even during her last illness, when

she was advised to decrease her workload, she would inevitably respond,

"I don't have time; I have too much to do."

The same rhythm and the same demands

were placed on her collaborators. Implacably.

During the early months of 1947,

Evita was busy creating her first weapons in defense of the poor: she

set in motion a children's tourism plan and the first contingent of workers'

children left for the hills of Córdoba on January 6, 1947; she

negotiated and gave out subsidies to assist in the construction of polyclinics

designed for workers in the textile and glass industries; she distributed

subsidies granted by the state through her mediation to more than 500

destitute families; she distributed clothes, food and household goods

to needy families. On January 20, 1947, she received a delegation from

Villa Soldati (a slum) which informed her of their unhealthy living conditions.

On the same day she visited their neighborhood, situated close to the

Flores marshlands. She personally took charge of implementing a plan to

provide residents with health care and social services as well as suitable

housing. On January 25, some families began to move into newly-constructed

modern chalets in Avellaneda while the rest of the families waited their

turn in emergency housing. On February 12th these families also moved

into housing provided for them by the municipal government on the 400

block of Belgrano Avenue. (Democracia, January 18, 1947).

From the beginning, Evita had aimed

for "direct social help": a job, medicine, housing. She would continue

throughout her few remaining years of life to create immediate solutions.

Simultaneously, Evita began to travel

to the interior. On October 26, 1946, she left for Córdoba where

two policlínicos were inaugurated. These hospitals for railway

workers had been constructed under the auspices of the Ministry of Labor.

On November 30 she traveled to Tucumán, a province in the north

of Argentina. Her reception was so enthusiastic that it exceeded the ability

of the authorities to control the crowds and some people were injured.

On August 21, the Senate approved

the project which would give women the vote. Evita went to the Chamber

of Deputies to meet with the leaders of the Peronista bloc. Their objective:

women's right to vote. She would return to the Chamber in the following

days to talk to the legislators of the Peronista Party. The campaign had

begun.

In

June of 1947, officially invited by the government of Spain, Evita began

a tour which would take her to Spain, Italy, Portugal, France, Switzerland,

Monaco, Brazil and Uruguay.

In

June of 1947, officially invited by the government of Spain, Evita began

a tour which would take her to Spain, Italy, Portugal, France, Switzerland,

Monaco, Brazil and Uruguay.

Acclaimed in Spain, she received

the country's highest decoration: the Great Cross of Isabel the Catholic.

In Italy she was received by Pope

Pius XII. The gold rosary he gave her would be placed in her hands at

the hour of her death. In Italy she did not always receive a warm welcome:

the Communist Party demonstrated its repudiation of her visit by shouting,

"Down with Fascism!" There were other protests along the way as the tour

continued, but the Communists' were the strongest.

In France she met the future Pope

John XXIII and gave a large donation to the victims injured in the violent

explosion which destroyed the Port of Brest. She also took time from her

schedule to relax.

Wherever she went, the official

itinerary of visits and receptions was interspersed with trips to workers'

neighborhoods and to their institutions. At the same time that she left

donations she sought to learn the lesson: what could Europe teach her

about social action?

Three years after her trip was over

she wrote, "With a few exceptions, on those apprenticeship visits, I learned

everything that institutions of social welfare should not be in our country.

The peoples and governments I visited will forgive me my frankness which

is direct and yet so honorable. On the other hand, they-peoples and governments-are

not to blame. The century which preceded Perón in Argentina is

the same century which preceded them." (Perón, Eva. op.cit.179).

After she returned from Europe,

Evita plunged back into her activities. Before she left she had begun

to fight for women's suffrage. The battle for women's right to vote started

many years ago and was fought within the framework of the worldwide battle

for women's emancipation. Argentina was not a pioneer. New Zealand had

given women the right to vote in 1893 and many nations had already followed

in her footsteps before Argentina's law 13010, passed in 1947, gave Argentine

women the right to equal suffrage.

Before leaving Madrid, on June 15,

1947, Evita addressed the women of Spain: "This century will not go down

in history as the "Century of World Wars" nor even as the "Century of

Atomic Disintegration" but rather as the "Century of Victorious Feminism."

The prediction has not come true; much remains to be done but obtaining

for women the right to vote remains a significant milestone.

In Argentina the struggle for women's

rights began with the turn of the century. The names Cecilia Grierson,

Alicia Moreau de Justo, Elvira Dellepiane, Julieta Lantiri, Carmela Horne

and Victoria Ocampo will be forever linked to this cause.

The feminist organizations of the

time were mostly made up of women from the middle and higher classes,

university graduates who had already begun in their own homes the struggle

to not to be limited by thetraditional roles assigned them by society:

to become wives and mothers.

The suffragettes presented bills

in Congress. Some were wide, some more restrictive and some had the support

of political figures like Alfredo Palacios: all were systematically buried.

The last one, dated 1938, was signed by Victoria Ocampo and Susana Larguía.

The methodology used by the feminists

was limited to the presentation of the bill, the pretense of a vote, the

distribution of consciousness-raising brochures. Compared to the English

suffragettes, for example, Argentine feminists' activity was extremely

moderate.

What was lacking was a projection

of their organizations beyond their own limits, a broad appeal addressed

to all Argentine women whose profile was very different from that of the

women who were petitioning in their name.

From the Secretaría, the

Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare, Colonel Perón took up

the political cause of Argentine women and created a Women's Work and

Assistance Division. The right of women to vote was again brought to light.

On July 26,1945, in a session of Congress, Perón specifically underlined

his support for the initiative. The Commission Pro Women's Suffrage was

formed and the government was petitioned to show its support for the Acts

of Chapultepec (in which those countries which had signed the Acts but

had not yet given women the vote agreed to do so).

The subject of women's right to

vote had been taken up by the government itself. A sea change was underway.

With the exception of the Argentine Suffragette Association, presided

over by Carmela Horne, the women's suffrage organizations opposed the

government's support of their projects. On September 3, 1945, the National

Assembly of Women, presided over by Victoria Ocampo, decided to reject

the vote given to them by a de facto government and to demand that the

Supreme Court assume the job of governing the country. The theme of the

Assembly was "Women's Vote Only If Sanctioned by a Congress Chosen in

an Honest Election."

Women's suffrage was once again

put on the back burner during the momentous events of October, 1945.

The electoral campaign of 1946 made

it clear that, whether they supported the Labor Party or the Democratic

Union Party and even without any political rights, women had become part

of Argentine politics. All they needed was to become a legitimate part.

As President, Perón returned

to the topic of women's suffrage in his First Message to Congress, on

July 26, 1946, and in the Five Year Plan. Within this framework, Evita

began her campaign. She worked from different vantage points: with legislators,

with the delegations who visited her, with the women congregated in the

civic centers, by means of radio and the press. For example, on September

17, 1946, she and women from different Peronista feminist organizations

drew up a common action plan. On January 17, 1947, she spoke to a delegation

of women educators from Rosario: "I'm fighting for women's right to vote

and I won't cease in my struggle until that right becomes a reality."

Beginning on January 27, every Wednesday

at 9:00 P.M. she broadcast a message from the Residence to all women,

urging them to join her the struggle for their rights.

When she returned from Europe-where she had alluded to the struggle on

several occasions-she found that the bill was still on the back burner.

Democracia published a "Letter

from Eva Perón to Argentine Women" in which she exhorted them to

fight twice as hard to quickly obtain the passage of the women's suffrage

law.

There

were two turning points in the history of this process: the entrance of

women into politics and the gaining of official support. A third can be

added: Evita addressed her message to a wide spectrum of women who made

the cause their own and began to assume an active role: they organized

meetings and published pamphlets. Working women took to the streets to

put up posters demanding the passage of the law. Feminist centers and

institutions declared their support. On September 3, when the law should

have been debated in the Chamber of Deputies, a great concentration of

women was convoked. The debate was postponed. A concentration assembled

again on the ninth. Evita, who could not be present on the third, was

inside the Chamber on the ninth. Outside, a multitude acclaimed her. Another

turning point: women began to see Eva Perón as their spokeswoman.

There

were two turning points in the history of this process: the entrance of

women into politics and the gaining of official support. A third can be

added: Evita addressed her message to a wide spectrum of women who made

the cause their own and began to assume an active role: they organized

meetings and published pamphlets. Working women took to the streets to

put up posters demanding the passage of the law. Feminist centers and

institutions declared their support. On September 3, when the law should

have been debated in the Chamber of Deputies, a great concentration of

women was convoked. The debate was postponed. A concentration assembled

again on the ninth. Evita, who could not be present on the third, was

inside the Chamber on the ninth. Outside, a multitude acclaimed her. Another

turning point: women began to see Eva Perón as their spokeswoman.

On September 23, amidst a gigantic

civic convocation in Plaza de Mayo, the law was passed.

The pioneers among the women feminists

rose up against the passage of the law, seeing it as a political maneuver

and not as a defense of the cause of all women.

Their slogan became "Now we don't want to vote."

But in 1951 they all voted, the

Peronista women and the "antis."

The sanction of Law 13010 set in

motion a series of events which would make it more effective. On May 23

the voter registration process began as outlined in article four of Law

13010. In 1951, with Presidential elections on the horizon, Evita, as

President of the Peronista Women's Party, sent a message to the Chamber

of Deputies, asking for amnesty "for that new sector of voters who have

not yet registered."

The road which led to women's suffrage

was arduous. The road towards civic capacitation and the preparation of

women so they could take part in the political struggle would be even

more arduous.

On September 14, 1947, the Peronista

Party reorganized so as to permit the formation of another Peronista Party,

exclusively for women (Partido Peronista Feminino-PPF).

The PPF would become a reality on

July 26, 1949. The first National Assembly of the Peronista Feminist Movement

met in the Cervantes Theater. There the Peronista Women's Party was born.

Its underlying principle would be its adhesion to the doctrine and person

of Perón. Evita was elected President with full organizational

powers. The internal structure of the PPF was monolithic: the President

of the party made the decisions and determined the direction of the work

to be undertaken.

"The organization of the Partido

Peronista Feminino has been for me," Evita wrote in The Reason for

My Life, "one of the most difficult enterprises which I have undertaken.

With no precedent in the country-something which I believe has been to

my good fortune-and without any other resource but a heart placed at the

service of a great cause, I called together one day a small group of women.

There were only about thirty. All were very young. I had known them as

infatigable collaborators in my work of social help, as fervent Peronistas,

fanatics in the cause of Perón. I had to ask great sacrifices of

them: to leave their homes and their jobs, to set aside one lifestyle

and take up a more difficult and intense one. I needed women like them:

untiring, fervent, fanatical. It was necessary to conduct a census of

the women of the whole country to find those who believed in our cause.

This undertaking would require intrepid women who were willing to work

day and night." (Perón, Eva: op.cit., pg. 228)

They were the census delegates who

also had the job of opening the "unidades básicas" (neighborhood

meeting centers). In January of 1950 the first unidad básica was

inaugurated in Buenos Aires, in the President Perón Neighborhood

in Saavedra.

The unidades básicas of the

Peronista Women's Party, besides being centers of political activity (they

were campaign headquarters during the 1951 Presidential elections), were

centers of social work. "The descamisados," she would say in her autobiography,

"do not distinguish between the political organization over which I preside,

and my Foundation. The unidades básicas are something which belongs

to Evita. And they go to them looking for what they hope Evita can give

them. They themselves, my descamisados, have created a new function for

the unidades básicas: inform the Foundation about the needs of

the humble people of the entire country. The Foundation attends to these

requests by sending help directly to those in need.I have been severely

criticized for this.My eternal super critics consider that in this way

I use my Foundation for political purposes. And maybe they are right!

The end result of my work does have political repercussions; people see

in my work the hand of Perón which reaches to the most remote corner

of my country... and his enemies cannot be happy with that consequence

of my work." (Perón, Eva:op. cit., 230-231).

The political action taken in favor

of women harvested its fruits in the elections held on November 11, 1951.

For the first time ever 3,816,654 women voted, 63.9% for the Peronista

Party,and 30.8% for the Radical Civic Union Party.The Peronista Party

was the only one to include women as candidates for election. In 1952,

23 women deputies and 6 senators took their seats in Congress.

If being a candidate on the ballot

is a right which has been acquired, being elected involves a continuing

struggle. Law 24012, passed in 1991, which establishes a 30% quota for

women in representative political positions, and provides clear evidence

of the discrimination which still pervades our society.

"Everything, absolutely everything

in our contemporary world," wrote Eva Perón in the middle of the

20th century, "has been tailored to the measure of men."

"We are absent from governments."

"We are absent from Parliaments."

"From international organizations."

"We are neither in the Vatican nor

the Kremlin."

"We are not part of the upper echelons

of the imperialist countries."

"We are not in the atomic energy

commissions."

"Nor in the great multinational

corporations."

"Nor in freemasonry nor in any secret

societies."

"We are not in any of the great

power centers of the world." (Perón, Eva:op.cit., 223-224)

Since then the world has undergone

profound and vertiginous changes but it is still made to the same measure.

Evita, whose concept of feminism

saw women as protagonists while continuing to be feminine, thought that

the feminist movement should, for love, be united to the cause and doctrine

of a man worthy of trust. She understood that among the many differences

between a man and a woman, one difference involved the concept of "action":

"A man of action is one who triumphs over the rest. A woman of

action is one who triumphs for the rest."

The "action for the rest"

had a name: Eva Perón Foundation.To this Foundation,

Evita dedicated her best efforts.

Mothers and

children found a refuge in the Hogares de Tránsito, temporary

homes where they stayed until work and a permanent home could be found

for them.

|

|

The social work which Evita began

in 1946 began to acquire far-reaching influence and importance. The Social

Help Crusade worked specifically to create neighborhoods of affordable

housing, Temporary Homes (Hogares de Tránsito), school food programs,

and to provide jobs to unemployed workers, instruments for hospitals,

mediation for the provision of water and sanitary facilities for low income

neighborhoods, donation of household items to needy families, and distribution

of toys to poor children, especially during Christmas and Epiphany.

The funds and the articles were

donated, especially by the workers' unions.

Also, the Social Work Crusade received

funds from the Ministry of Social Welfare which were destined for the

purchase of clothes, shoes, food, and medicine.

Evita's special position in the

power structure (power from the outside) permitted access to the place

where the decisions were made involving projects or increasing workers'

rights. Her position permitted her to take action outside the bureaucratic

structure.

By the end of 1947 it was clear

that her social action required an organic structure.

To

Be Evita ©

Biography

Evita Peron Historical Research Foundation

Translation by Dolane Larson

Hecho el depósito que marca la ley 11.723

May not be reproduced in total or partial form

without authorization of the FIHEP

April, 1997